Under the hood of Go's context

This post is dedicated to you if you had used the Go programming language and ever wondered “What is a context anyway?”.

context is a package in Go’s standard library. I think context is idiomatic Go, hence I find quite some external packages and standard library packages using it.

You can read all about it from here - https://golang.org/pkg/context/

What I am trying to do here is just walk through the implementation details of the context package by reading the source file of it.

I can’t guarantee if you could fully follow my writings here. But, I just want you to leave with a mindset that “Internal implementations of OSS software are always accessible for anyone to read. We just have to make time for it!”.

Giving the link to the source file of the context package, just in case if you want read the source directly and understand it in your style.

What is it?

Bare minimum, copy pasted from the docs.

Package context defines the Context type, which carries deadlines, cancellation signals, and other request-scoped values across API boundaries and between processes.

It can usually be seen as the first argument to a function call.

1 | func DoSomething(ctx context.Context, arg Arg) error { |

When should you use it?

There is this interesting one-liner from the docs,

Incoming requests to a server should create a Context, and outgoing calls to servers should accept a Context.

So if you are buiding a server or client application in Go, then you will have to deal with contexts.

That leads to why it has the following concurrent nature.

The same Context may be passed to functions running in different goroutines; Contexts are safe for simultaneous use by multiple goroutines.

It is mainly used for propagating a request’s state across function calls.

I am going to ask a “Sorry” and silently try to assume its usage feels like the req object in express middlewares

You have to skip reading this stuff if you are not looking to read JavaScript.

1 |

|

Note how we pass in data across function calls using the req object. I think a context has similar functionality.

How to and How not to?

Always propagate contexts as arguments to function and don’t store it in a struct. That’s some bulletproof wisdom from docs for you! :D

Pass context.TODO if you are unsure about which Context to use.

The above one-line statement is probably what triggered me to do this deep dive - Why are people (myself included) becoming unaware of what context to use?

Do not pass a nil Context, even if a function permits it.

That is enough copy-pastes from the docs.

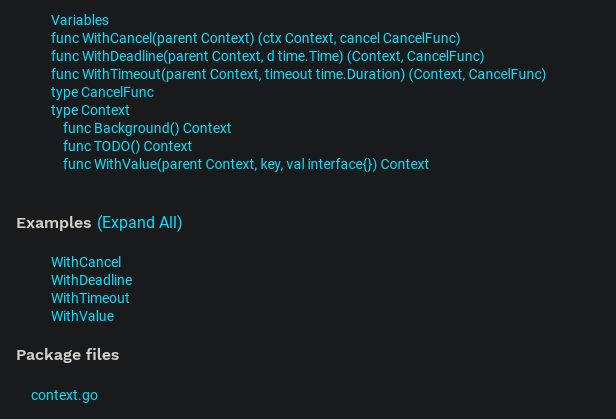

API

That is all of context for you!

The interface

At its core lies the Context interface. it is the object that gets sent around. woah! I always imagined it to be struct. Now it is interesting to note that it is an interface.

1 | type Context interface { |

This seems to accomodate the information used by various API methods of the context package.

Errors

context package defines errors which are returned by the Err() method if the channel returned by Done() is closed. This error message is used to communicate what made the channel close.

1 | var Canceled = errors.New("context canceled") |

Empty context

Next up is an empty context. It is a context with no value, no deadline and is never cancelled. Lets see how it is defined and where it is used.

1 | type emptyCtx int |

Now that we have an empty context. It seems like both context.Background() and context.TODO() return an empty context. So when you are creating a context this is probably where we start.

1 | func Background() Context { |

Cancel Context

Things start to complicate from this point onwards. Now that we have some empty contexts that could be used as the starting point / parent for other kind of complex contexts such as context with cancel/deadline/timeout.

Here we will try to explore the inner workings of context.WithCancel.

1 | func WithCancel(parent Context) (ctx Context, cancel CancelFunc) |

By the looks of its method signature, it is obvious that “it takes in a parent context and gives back a cancellable context”.

In that method definition, we know that the Context is an interface type and we notice that there is a new type called CancelFunc. Let’s see the definition of it.

1 | // A CancelFunc tells an operation to abandon its work. |

It is a simple function that takes 0 argument and returns 0 values.

Now let’s dig in the definition of the WithCancel method.

1 | // WithCancel returns a copy of parent with a new Done channel. The returned |

The important thing to note here is the comment above the method.

Note that the returned context’s Done channel is closed either by calling the returned CancelFunc or if the parent context’s Done channel is closed.

cancelCtx

So as you see, the first step in the WithCancel method is creating a cancel context c := newCancelCtx(parent)

1 | func newCancelCtx(parent Context) cancelCtx { |

It just wraps the context in a struct called cancelCtx and returns back it. So now on to the definition of cancelCtx struct.

1 | // A cancelCtx can be canceled. When canceled, it also cancels any children |

Interesting point here is the presence of mutex that guards the other values of the struct. This mechanism is the one that makes the context package implementation to be concurrent.

We note that there is a type called canceler used inside the struct, so checking the definition of it.

1 | // A canceler is a context type that can be canceled directly. The |

Before we move on the the other parts of WithCancel function call, we will try to look at the implementation of cancelCtx struct. It seems to implement these interfaces: Context, canceller and stringer

Err()

It seems to be just a wrapper for the err field in the cancelCtx struct in a thread-safe way.1

2

3

4

5

6func (c *cancelCtx) Err() error {

c.mu.Lock()

err := c.err

c.mu.Unlock()

return err

}

Done()

Again a thread-safe wrapper for accessing the done field. but at the same time, it seems to create a new channel for the context if it is not already present.

1 | func (c *cancelCtx) Done() <-chan struct{} { |

Value()

This seem to just return the value of parent context.1

2

3

4

5

6func (c *cancelCtx) Value(key interface{}) interface{} {

if key == &cancelCtxKey {

return c

}

return c.Context.Value(key)

}

propagateCancel

So we have a new cancelCtx on hand right now and it is being passed down to propagateCancel. This just propagates cancel from the parent context to our context. If the parent’s Done channel is closed, then I think this function takes care of propagating that to the current context and make Done channel of current context closed.

First we check if the parent’s Done returns nil. If the parent context is also a cancelCtx and have Done called, this wouldn’t be nil. This might be a little confusion, but see the implementation of cancelCtx’s Done function to understand what it means to do the following nil comparison.

1 | done := parent.Done() |

After that we check if the parent channel is closed. If it is closed, then we cancel the child using the cancel method. We will see the implementation of cancel method in a short while.

1 | select { |

If the channel is not closed, then we fallthrough the logic of the function. After that our flow takes two paths.

1 | if p, ok := parentCancelCtx(parent); ok { |

parentCancelCtx is the function that returns an underlying cancelCtx from the given parent context.

1 | func parentCancelCtx(parent Context) (*cancelCtx, bool) { |

After getting the cancelCtx, we seem to error out if p.err is non-nil. If the err is nil, then it means that there is a valid parent cancelCtx for which the current cancelCtx should be added as a child. We basically use a set to track the children.

1 | if p, ok := parentCancelCtx(parent); ok { |

If it doesnot seem to have a valid underlying cancelCtx, we just spin up a goroutine that listens for either of the parent of child to be close its Done channel. We also seem to track the count of this in a variable.

1 | atomic.AddInt32(&goroutines, +1) |

cancel

Next up, we closely examine the cancel function of the cancelCtx

1 | // cancel closes c.done, cancels each of c's children, and, if |

The code here is pretty self-explanatory. One supplement here is to add the implementation of removeChild method which is also a very simple, “delete from set” operation.

1 | // removeChild removes a context from its parent. |

WithDeadline

Next up is context.WithDeadline which gets cancelled by calling the returned cancel method or if the context crosses a time deadline. It is comfortably built on top of the cancelCtx

We will start with the method definition. It accepts a parent context and returns back a context and CancelFunc

1 | func WithDeadline(parent Context, d time.Time) (Context, CancelFunc) |

Here is step 1.

1 | if cur, ok := parent.Deadline(); ok && cur.Before(d) { |

In order to decipher this stuff, we will look up the doc of Deadline method in Context interface.

1 | type Context interface { |

so the code in step 1 translates to “If the parent context has a deadline set && if the parent’s deadline is before the current deadline”, we return back the parent using WithCancel(parent). Because in this case, the parent would expire first, thus resulting in cancelling the child context automatically.

After that, we know that the deadline of the current context occurs before the parent context. So this is what we do.

1 | c := &timerCtx{ |

Let is explore the definition of timerCtx.

1 | // A timerCtx carries a timer and a deadline. It embeds a cancelCtx to |

As the comment says, its Err and Done implementation come from cancelCtx. Apart from that let us explore the methods associated with it.

1 |

|

Now that we know the details of timerCtx, we can go back to exploring the WithDeadline method. After having a timerCtx, we propagate the cancel from parent to children.

1 | propagateCancel(parent, c) |

This method is the same used before in cancelCtx. This adds the behaviour of “If the parent’s Done channel is closed, then the children’s done channel will also be closed.”

Next we calculate the duration of the deadline for the given context.

1 | dur := time.Until(d) |

If the deadline is gone, then we immediately cancel the context and send back the context. Now if there is a valid duration, we will cancel the current context after the given duration.

1 | c.mu.Lock() |

At the last we return back the context and cancelFunc

1 | return c, func() { c.cancel(true, Canceled) } |

WithTimeout

Now this becomes easy-peasy. Write a wrapper on top of WithDuration.

1 | // WithTimeout returns WithDeadline(parent, time.Now().Add(timeout)). |

WithValue

We are coming close to doing this fully! We can read WithValue implementation in one go. It is a mix of Context and key-value pair.

1 | // WithValue returns a copy of parent in which the value associated with key is |

Done

uff, finally we are done with this blog post. It stretched longer than I expected. Most of the times I used to be afraid of the context pacakge in Go whenever I see it in some library. Now, this excercise has given me better context about the context package and probably make me less scared about using it.

I was surprised that I was naturally able to predict that there should be something like “context leak” while reading through this exercise. Hmm, so that’s for now. I would like to write about practical use case of the context API in real world codebases if I get the chance to!